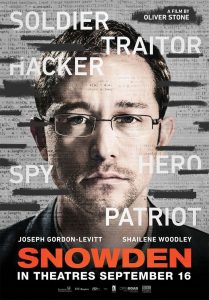

Did you miss Rodrigo Barahona’s discussion of SNOWDEN at The Coolidge Theatre on Tuesday, September 20, 2016? Read below to see what got the conversation started:

If this film were on my couch, these are the words that would come to my mind as I listened to its story:

Idealization

Voyeurism

Exhibitionism

Boundaries

Privacy

The self

Paranoia

Fantasy

Reality

Sexuality

Murder

Fathers

Sons

Omnipotence

Omniscience

Good

Bad

Angelic

Evil

We might say that in some ways, the structure of Stone’s narrative follows the common anxieties of a child transitioning from innocence to growing complexity in his experience of the world. We start with Snowden being a young idealist, who doesn’t seem to notice or mind the unsavory actions of his government and views himself as part of a larger, beautiful, and all good nation where the big problems are not really reflected on and even less criticized, but just accepted as the way things are from the point of view of his reality. His girlfriend, Lindsey, has her own ideas, but he writes them off initially as just “her reality”. So he is safe in his image of being an all-good warrior fighting in the name of, and in some ways fused with, the all-good and powerful country. My country is good, and I am good.

Like a child with his all-powerful and all-loving parent, there is safety and identity in this illusion. When he breaks his legs, and there is a threat of separation, he is disappointed, but not deterred.

Gradually, through the influence of Lindsey, and like the child with the parent, he is led by the hand and shown that the world is neither black nor white but much more complex and troublesome. This includes understanding more about the relationships between people including boundaries and how power is distributed among the members of a couple and by extension society. Eventually, like the child becoming aware of the disappointing and at times disturbing realities of the parents, or like the adult becoming aware of the total personality including disturbing parts of their partner (we have a sense that Snowden is never at ease with Lindsey’s expressions of sexuality), Snowden experiences an existential crisis, where his perception of himself becomes directly affected by his perception of the government and the president. What does it say about him that he works for a government that behaves in this way? Snowden begins to understand that the beautiful and good parent he had in his government has other interests and that these are nefarious, a stark contrast to his idealized belief that they were out to save the world together.

Instead, he realizes, what has been happening (we sense that Snowden had been denying some of this reality to himself and perhaps took too long to comprehend what the government would do with his program) is that the protector is at the same time an abuser who, in addition to protecting its children, has its own designs (desire) for them.

He digs deeper and finds disturbing information about these real intentions, the “real” mind of the government and suddenly is catapulted into a hostile and paranoid world.

We now have Snowden against the United States Government, and with that the fulfillment of a wish to abolish the tyrannical authority, and establish an symmetrical, liberal and democratic community of siblings where everyone debates in a healthy and thoughtful way and all voices and needs are heard and accommodated. A very good family. The right for safety along with, and not at the cost of, privacy. The right to be alone with another, to be held in the safety of a relationship or of the community, but without forfeiting the boundaries or the privacy of the self. Now, I think Freud would have called this an illusion, that to live in Society or Civilization one necessarily has to sacrifice some cherished individual liberties in favor of the common good, although Snowden’s ideas about what the common good differs from those of his mentor and symbolic father in the film, Corbyn. This is an issue that has come up in real life about Snowden’s actions, and for which he is criticized-the fact that he took it upon himself to judge what was in the common good. Against the authority who excessively conceals, Snowden now becomes the authority who excessively reveals.

Back to our fantasies, and voyeurism. What do we imagine the government will see when they peep through the cameras of our iphones? Are we really worried that they are going to see us downloading instructions for a bomb, or shaking hands with a terrorist? It is very interesting that Oliver Stone chooses to show the NSA operatives looking at sexual scenes, sexual images. Why is that? Does that not tap into our basic human anxieties? Doesn’t sexuality still trouble us today in the year 2016 as it did in Freud’s day? And what else can we gaze at through the NSA voyeur’s lens: drone strikes, murder. The stuff that we keep away from ourselves but cannot keep away from the NSA, Stone suggests, is the stuff of desire—murderous and sexual.

I think one of the most interesting scenes is when we see the young woman who is the drone pilot killing people. Watching her I felt the strange sensation that she was “one of us”, a young person, perhaps idealistic too. The strange implication of this is the idea that she may be fulfilling our own deep and dark wishes of power, omnipotence, and vengeance, and thus helping keep away our helplessness and terror. As long as we don’t watch films like this one, we can safely believe that the drone pilot is not us. So what startles Snowden when, in another scene, he notices the eye of the camera on his laptop while he and Lindsey are having sex is his own gaze, the terrifying glimpse of the innermost darkness in himself.

So, on the theme of the sexual: as I noted above, the viewer gets the sense that Snowden is never really at ease with Lindsey’s profession, for example the nude portraits, and problems in their sex life are hinted at—she says at one point that he “doesn’t touch” her. Something troubles Snowden about Lindsey, the two seem like opposites in more than one way—as characters in a Hollywood film and very much caricatures, she is painted as exhibitionistic, full of life, sexuality, warmth, sunshine and outdoors while he is reclusive, pale, and doesn’t seem to like to be in the spotlight in any way. She is life drive, striving for maximum stimulation; he is death drive striving to disappear into the ether of the cyber world.

We mentioned voyeurism. Snowden’s girlfriend now opens an interesting window into our own exhibitionism. Setting aside the obvious associations between her profession as a pole dancer and exhibitionism, her attitude of “who cares” is understandable and demonstrates how easily we’ve come to this point: we already share everything on social media out of a not so unconscious wish to be seen by the other. The gaze of the other is already upon us in our minds and that is the way we like it. I know many people, for example, who already assumed the government had access to everything, although this film makes it clear that it is not necessarily the fact of the Other’s gaze that is startling but the exercising of that gaze upon us without our control and permission, which raises the anxiety producing question of, “What will they find out about me that even I don’t know?”

The question of fathers and sons, and therefore the Oedipal father is also one that comes to mind. To grossly simplify the concept of the Oedipus Complex, the idea is that one of the hardest developmental tasks that a child has to master involves processing the realization that the parents are into each other in a very different way than they are into the child, and that the child is excluded from that relationship. Quite naturally, rivalry at different moments with both parents ensues, and ultimately, if all goes well, disillusionment and the understanding that the child needs to move on to other people outside of the family happens. But it never really goes well and most of us continue to fight this conflict in our minds with other people as stand-ins all of our lives.

A finer point is that it slowly dawns on the child that this parent, or Other is interested in the other parent’s desire, which the child begins to experience disturbingly as linked to sensuality and sexuality, that is, something that the child does not understand and therefore has no access to and cannot thus wield in his favor. In effect the system is rigged, as Bernie Sanders would say. Sexuality then becomes a traumatic, so to speak, idea around which the child begins to experience conflicts related to his parents. Up to this point, the child loves both parents but wants to be the sole focus of each one. The child begins to realize that the parents do not hold it solely in mind but desire each other in a different way than they do the child. Each parent lays claim on the object of the child’s affection: the other parent. And a brutal, internal, conflict ensues where the child and the parent—this in the child’s mind—become rivals for the love of what is now a mutual love object. So, in the case of the little boy who takes the mother as the love object, the father is now the supreme rival, and one of the things that the child becomes aware of is the asymmetry in their relationship, and out of this grows a deep sense of unfairness in his circumstances. And a disillusionment in the world and his place in it. Indeed, the primal father, as Freud calls him, or the father of the horde, the horde being the mythical first family of our primitive ancestry, is the ultimate alpha male, who is omnipotent and omniscient, and has exclusive rights to sexual power over all the members of the horde. In the film, he hunts and drinks beer with the submales in the group, some of them dressed in red outfits and acting as servants.

In light of this, it is interesting that Snowden is compelled to take action at the point that he understands that his symbolic father, Corbyn, has cast his omnipotent and desirous gaze on Lindsey. When Corbyn tells him, in what to me was the most paranoid scene of the film, “don’t worry, she’s not sleeping with the photographer”, what he is also saying is, “I know her better than you. I enjoy a relationship to her that you are excluded from”. It is at this point that the son attempts to overthrow the father and reveal to the world what a fraud the father really is, and that his power depends only on his symbolic position of authority and nothing else.

Through consensus (a jury of the people, as opposed to a secret military tribunal) the father loses his power.

This theme reappears with the paranoid fear that Lindsey is having an affair with a photographer, someone who also gazes at her with his lens, takes photographs of her and captures something of her that Snowden can not see and have access to. Again, the father’s and the parent’s sexuality.

So, the father. This archetypal father, the primal father as both Darwin and Freud theorized him, is not overthrown by one son but by a “band of brothers”. In saying primal father what is implied is that in fighting against our fathers we are joining our ancestral siblings fighting against all fathers, everywhere, throughout all of time. It is a group effort, and this is what endows the crime with a sense of justice, and after the father’s murder, legitimacy and the establishment of civilized society. (So as the story goes, in the original family of the primal horde, the brothers band together to overthrow and murder the abusive, all powerful father. They then eat his body and as you can imagine feel a tremendous sense of guilt. In order to ease their guilt and to ensure that this kind of thing never happens again, they build a totem in his name, which they proceed to worship, and begin setting down laws regulating the relationships between people, and so we have the origins of religion, law and order and civilization). So Oliver Stone has to include that Snowden’s two friends at the NSA knew what he was about to do and let it go, presumably because he was fulfilling the wishes that they did not have the courage to carry out themselves. One of them even helps Snowden by hiding his thumb drive under his foot. These scenes weren’t necessary to the Snowden narrative, in fact, we hear many times from Snowden that he made sure not to implicate anyone but himself in the crime. So why do it now in the film? I think it is because these character’s complicity is necessary for us the viewer to identify with Snowden’s actions. They remind us of our anxiety and reassure us that in sympathizing with him, we are not the crazy ones and that we remain, at least in phantasy, on the right side of history and still within the realm of righteousness, at a time when the very limits of law and order are being tested so persistently. So the film ends with the primal horde again, the band of brothers and sisters at the conference around the new father, Snowden, elevated to the status of cyber-totem—a soul trapped inside the metal body of this robot that takes questions from the moderator and the crowd. The question that the film then raises becomes “What do we do next as a society?” Do we turn Snowden into an angel, someone who at the film’s end is portrayed with the glowing white light of immaculate and lonely exile in freezing cold Russia behind him, effectively dividing up the world into good guys and bad guys? Do we murder and eat Edward Snowden, condemn him to life imprisonment or the virtual limbo world he inhabits now, only to, at a later time and out of guilt and terror of our own darkness effect the changes that he warned us about? These are the questions that came to my mind as I listened to this film.