The following piece was adapted from remarks initially delivered on February 21st, 2017 following a screening of the documentary “I Am Not Your Negro” at the Coolidge Corner Theatre. It was first printed in the Spring/Summer 2017 edition of the BPSI Bulletin, which can be read here. The “Off the Couch” series will resume Thursday, September 19th.

Michele Baker, MD

I was sympathetic to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Of course I was. I’m a liberal.

But I wasn’t…afraid. I have two boys. They are, respectively, around the age Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice were when they were murdered. But my boys are white. Very white: One is blond, the other a redhead.

I am white, too. When I was pulled over for driving with my headlights off late at night in Brookline a couple of years ago, with my hockey bag in the backseat and my hockey stick jutting out over my shoulder, I was confident that the police officer would be polite, maybe even friendly. Maybe even a hockey player. In fact, he was helpful and patient as I fumbled for my registration, and then sent me on my way after ascertaining that I lived in the neighborhood.

In November, when the Electoral College went Republican, I began to feel the shock I hadn’t felt since I was a young person in Hebrew school facing for the first time the realities of the Holocaust. I became pretty obsessed with the subject. At my fancy prep school, ninth graders were required to give a 10-minute talk. Typical topics in my year were “Toothpaste” and what it felt like to have your parents own one of the most expensive restaurants in Boston. My subject was “The Holocaust.” But even then, it felt almost theoretical, so long ago and far away. Though I did lose family members, they were from my grandparents’ generation, and all my grandparents had been in this country since the early 20th century. I knew about Nazi Germany, and yet I was still stunned when Trump won.

On November 9, I went out for consolation and drinks with my friend Laura. She’s been a union organizer since we graduated from college. She’s a tall white girl, but her husband and daughter are Hawaiian. She was devastated that night, worried about her seven-year-old girl. She told me, with her classic self-deprecating humor, that many of the folks in the union, people of color, had been mocking her earlier. “Oh!” they said. “White girl is sad…” They weren’t shocked. They were used to it. They hadn’t been blinded by good times and optimism. They hadn’t been counting on generations of living in houses with white fences and going to college and buying Plymouths and having children in smocked dresses who would grow up with the same luxuries. James Baldwin points out in the film that white people had been able to do just this for years in mid-century America.

In his essay “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the 100th Anniversary of the Emancipation,” James Baldwin writes: “These innocent and well-meaning people, your countrymen, have caused you to be born under conditions not very far removed from those described for us by Charles Dickens in the London of more than 100 years ago.… I know the conditions under which you were born, for I was there. Your countrymen were not there and haven’t made it yet.” I believe he meant that white people did not know, did not understand because they hadn’t been forced to. This ignorance is the idealistic fantasy of race neutrality offered by the old white Yale professor on The Dick Cavett Show to whom Baldwin responds with an explanation of his visceral, embodied fear.

This is white privilege.

Now, to some—albeit a much lesser—degree, it’s in my house, too. My 13-year-old doesn’t sleep through the night anymore. He’s scared and angry. He comes into my bedroom at 2:30 or 3 a.m. and talks to me in rapid fire about the latest outrage he’s heard and read about. Did I know that the Dick and Betsy DeVos Family Foundation gave millions of dollars to organizations that support conversion therapy? He can’t believe it. We can’t believe it. The bullies won. The bullies won?

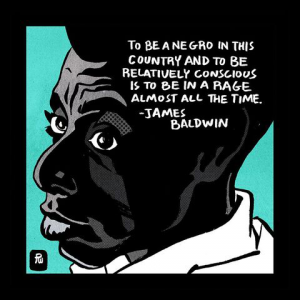

I don’t think James Baldwin would be too surprised. In Haitian director Raoul Peck’s documentary I Am Not Your Negro, Baldwin speaks to us in his own voice and through Samuel L. Jackson’s. He tells us, the audience, what it is like to always have had to get it. To feel rage not as an adult for the first or second time, but always, once you’re old enough to look in the mirror.

In the introduction to his book Notes of a Native Son, Baldwin writes: “The rage of the disesteemed is personally fruitless, but it is also absolutely inevitable; this rage, so generally discounted, so little understood even among the people whose daily bread it is, is one of the things that makes history. Rage can only with difficulty, and never entirely, be brought under the domination of the intelligence and is therefore not susceptible to any arguments whatever. This is a fact which ordinary representatives of the Herrenvolk, having never felt this rage and being unable to imagine it, quite fail to understand.”

After yet another of his friends, Martin Luther King Jr., was assassinated, he tells us, he wept “tears of helpless rage.” This is the rage that propels the Black Lives Matter movement. This is the rage I did not feel personally. This was the limit of my empathy. Chris Rock, during performances on his Total Blackout tour, says of the current political landscape: “I’m not scared. I’m black. The future is always better when you’re black.” When the audience laughs, it’s because we understand. We get it. And this is what comedy and film can do. When we sit in the theater immersed in the sounds and sights, our mirror neurons start working. I think Peck is fully aware of the power of movies—he shows us clips from dozens of films, building up in us a semiotic experience of the world through his eyes.

Here is Peck in an interview he gave: “As a black person and as a third-world person…I don’t have my own narrative in this medium, which is cinema. Since the discovery of cinema others have been the one telling the story.… A Native American could redo all the John Wayne westerns from a different perspective. This is what we don’t have; we don’t have our own visual history. So being a filmmaker for me was also trying to save part of our memory, part of our images, part of our stories. I saw it as one of the responsibilities I have—to make sure that we are not totally dead in the picture.”

Watching this film helps us build our empathy. Analysis requires us to emphatically join in another person’s psychological experience. On this topic Juan Tubert-Oklander writes: “True psychoanalytic empathy…requires both a sympathetic openness and an acceptance of the patient’s subjectivity and its impact on the analyst .… Consequently, the analyst must keep a dialectic tension…between an uncritical empathic resonance and an analytical inquiry of the experience that is thus harvested.” In the “Portrait” section of his film, Peck shows us old photos of African American people and then brings the photos to life, by showing contemporary people of color. The subjects look out at us, reversing the gaze. Baldwin tells us that black people have been looking at white people for centuries; now we look back, and thus look more closely at ourselves.

It is not enough to feel sympathy for another’s experience, to look through the mists of time at people long gone, people we had nothing to do with. Analysts, or in this case the audience, or perhaps white people in general, must do the work to know ourselves. We must look in our own mirrors. I initially felt deeply uncomfortable being the discussant for this film. But then I thought, why should only people of color have to do it? I need to own my role here as well, to speak from my experience. James Baldwin—brilliant writer, philosopher, and raconteur—tells us this. American history is built on the slave trade. American history is race history. He reminds us that whiteness is an invention. Whiteness is a consolidation of power, a signifier like “the Chase Manhattan Bank.” There are no white Americans without black Americans. It is our job, it is my job, to know myself, to know whiteness, and to look at it and to speak to it, and of it.

* * *

The opinions or views expressed on the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute (“BPSI”) social media platforms, including, but not limited to, blogs, Facebook posts and Twitter posts, represent the thoughts of individual contributors and are not necessarily those of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute or any of its directors, officers, employees, staff, board of directors, or members. All posts on BPSI social media platforms are for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as professional advice.

BPSI does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness or completeness of information contained in its contributors’ posts and/or blog entries, or found by following any linked websites. BPSI will not be liable for any damages from the display or use of information posted on its website or social media platforms. BPSI cannot and does not authorize the use of copyrighted materials contained in linked websites.