Dr. Michele Baker is a graduate and psychoanalyst member of BPSI. Her remarks below originally appeared in the Fall-Winter 2017 issue of the BPSI Bulletin.

Dr. Michele Baker is a graduate and psychoanalyst member of BPSI. Her remarks below originally appeared in the Fall-Winter 2017 issue of the BPSI Bulletin.

My husband is a rabbi. He was raised Episcopalian and converted, so he is Jewish, but not exactly in the same way I am. He didn’t have Jewish grandparents who paid him to eat the three cardinal food groups: milk, eggs, and bananas. He didn’t go to Jewish summer camp. And he wasn’t raised to hate Germans. So of course, as the chaplain at a Jewish Senior Life housing facility, he thought it was a perfectly lovely idea to invite the volunteer who works with him to our house for Sukkot. Her name is Johanna, and she comes from Germany.

I was prepared to cringe at her accent and to judge her innocent do-gooder privilege. But she was lovely—polite, calm, helpful, and interested. And so very young—18 years old, just a couple years older than my high school–age son. I wasn’t expecting to like her so much.  As the evening spun toward the personal and intimate, and fueled by the liquid courage of a couple glasses of wine, I opened up a confessional conversation with Johanna. I told her how weird it was for me to have someone from Germany sitting in my yard and yet to feel so warmly toward her. I told her that I was raised to hate Germans and mistrust them. She listened attentively, silent for a while, and finally said, “Yes, I would probably feel the same way.”

As the evening spun toward the personal and intimate, and fueled by the liquid courage of a couple glasses of wine, I opened up a confessional conversation with Johanna. I told her how weird it was for me to have someone from Germany sitting in my yard and yet to feel so warmly toward her. I told her that I was raised to hate Germans and mistrust them. She listened attentively, silent for a while, and finally said, “Yes, I would probably feel the same way.”

Instantly I felt better. I felt unburdened of the meanness inside me, freed from the nasty thoughts, which intellectually I had long recognized as without merit, but which still held such hovering internal power. It was a powerful experience to be validated by a teenager. Through our interpersonal connection, Johanna and I had escaped from a stratified system in which there was good and evil, victim and perpetrator, into something more complex and nuanced. In his classic 1979 paper On Projective Identification, Thomas Ogden writes, projective identification refers to “a group of fantasies and accompanying object relations having to do with the ridding of the self of unwanted aspects of the self; the depositing of those unwanted ‘parts’ into another person; and finally, with the ‘recovery’ of a modified version of what was extruded” (Ogden, 1979, p. 357). Johanna had helped me to integrate my hateful feelings in this way.

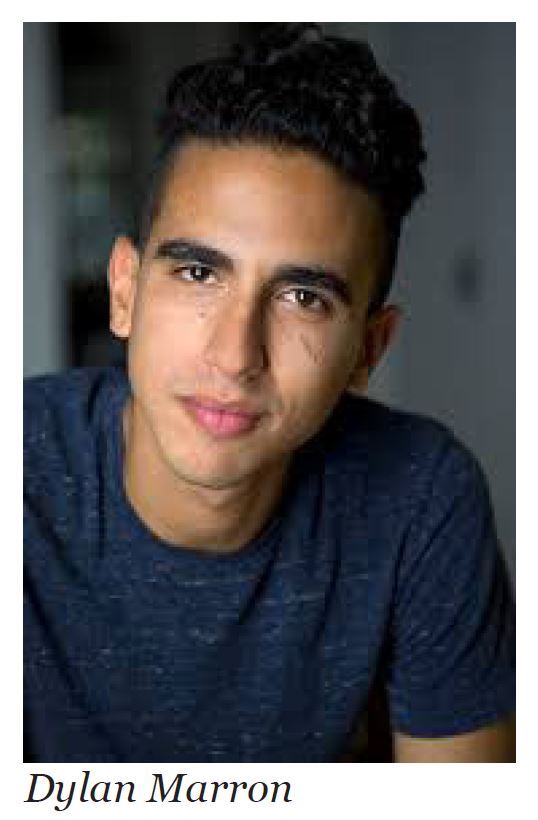

In his video and podcast work, the social activist Dylan Marron cleverly satirizes our current reality. In his Every Single Word series, he edits popular movies down to the words spoken by people of color. The words spoken by nonwhite actors in the entire Harry Potter oeuvre of eight films take six minutes and 18 seconds to unspool. In his Unboxing videos, he satirizes the beloved YouTube staple of “unboxing” products C like tech items or high-end handbags, subbing in concepts such as “Privilege” and “Liberal Elitism”—and sparing himself least of all in the process. Some people seem to both hate his work and hate him, calling him, in online comments, “a piece of shit,” “condescending as fuck,” and a “flaming homo,” as well as other less kind and thoughtful invective.

In his video and podcast work, the social activist Dylan Marron cleverly satirizes our current reality. In his Every Single Word series, he edits popular movies down to the words spoken by people of color. The words spoken by nonwhite actors in the entire Harry Potter oeuvre of eight films take six minutes and 18 seconds to unspool. In his Unboxing videos, he satirizes the beloved YouTube staple of “unboxing” products C like tech items or high-end handbags, subbing in concepts such as “Privilege” and “Liberal Elitism”—and sparing himself least of all in the process. Some people seem to both hate his work and hate him, calling him, in online comments, “a piece of shit,” “condescending as fuck,” and a “flaming homo,” as well as other less kind and thoughtful invective.

In his newest project, Conversations with People Who Hate Me, Marron has lengthy, serious but cheerful chats with his critics. In a series of podcasts, which I experience as earnest, radical, and hilarious, he allows himself to calmly inhabit the role he has been painted into by his harshest critics. He phones the people who have excoriated him online and invites them to talk. He asks them why they hate him, but also what their lives are like and what they were thinking and feeling when they left their comments and diatribes.

In his newest project, Conversations with People Who Hate Me, Marron has lengthy, serious but cheerful chats with his critics. In a series of podcasts, which I experience as earnest, radical, and hilarious, he allows himself to calmly inhabit the role he has been painted into by his harshest critics. He phones the people who have excoriated him online and invites them to talk. He asks them why they hate him, but also what their lives are like and what they were thinking and feeling when they left their comments and diatribes.

Not surprisingly, on the phone the haters are more thoughtful and self-aware than their online personae. More than one admits to having been drunk when he trolled Marron. Still, they have the courage to stand by some of their criticism, and Marron takes the analytic approach of being interested in their perspective without voicing immediate or overt criticism. He accepts with curiosity their point of view and, at least temporarily, allows himself to be the hated other, just as the analyst allows herself to be responsive to her patients’ projections and transference experiences.

In “Episode 1: You’re a Piece of Sh*t,” Marron talks to Chris, a self-proclaimed enemy of “social justice warriors.” Chris, as it turns out, supports gay marriage, but finds “LGBTQ-whatevers” to be silly in demanding “special rights.” The two men continue talking about a range of topics, including Black Lives Matter, the training of police officers, and the definition of a “racist.” Chris is a fan of fossil fuels and thinks global warming is “fake news.” But he does support affirmative action and ends up conceding that he doesn’t know what it’s like to be black. Marron mildly interjects some facts, suggesting, for example, that the KKK has more members than “30 guys down south in pickup trucks,” as Chris has dismissively claimed. Marron seems to try to find a way to meet Chris where he is, proposing that the “undocumented immigrants” Chris disdains might be in search of the benefits of the “American way of life” that both Marron’s and Chris’s ancestors came to the United States to find. When Chris asks, “What rights do gays need that they don’t have now?,” Marron says, “Well, I can tell you…if you want to know.” He proceeds to answer, then refocuses on Chris, saying, “But I’m curious to hear what you think…” By the end of the half-hour episode Chris is telling Marron, with laughter in his voice, “I no longer hate you!”

Freud, S. (1914). Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through (Further Recommendations on the Technique of Psycho-Analysis II). In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 12, pp. 145–156).

Ogden, T.H. (1979). On Projective Identification. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 60, 357–373.

Michele Baker, M.D., is a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and graduate of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute (BPSI) and the Harvard Longwood Psychiatry Residency Training Program. She practices in Brookline.

Michele Baker can be contacted by email here.

***

The opinions or views expressed on the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute (“BPSI”) social media platforms, including, but not limited to, blogs, Facebook posts and Twitter posts, represent the thoughts of individual contributors and are not necessarily those of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute or any of its directors, officers, employees, staff, board of directors, or members. All posts on BPSI social media platforms are for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as professional advice.

BPSI does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness or completeness of information contained in its contributors’ posts and/or blog entries, or found by following any linked websites. BPSI will not be liable for any damages from the display or use of information posted on its website or social media platforms. BPSI cannot and does not authorize the use of copyrighted materials contained in linked websites.