Ellen Goldberg, PhD, is a Child Neuropsychologist and a Psychotherapist Member of BPSI. Her remarks below originally appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of the library newsletter, which can be read here.

In many ways, Trevor Noah is a remarkable comedian. He dances on a tight rope while he explores real life hardships, political discontent, and humor. I occasionally watched his show and other late-night comedians during the pandemic. His comedic colleagues seemed somewhat flummoxed and I wondered if they were having trouble because there was no audience. Trevor didn’t seem to mind the isolation. So, I decided to read his memoir.

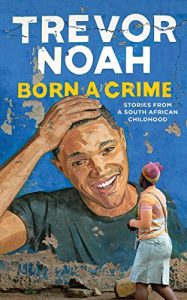

I didn’t fully get the meaning of Born a Crime until I read the book. Trevor Noah was born on February 20, 1984 to a black South African woman, Patricia Nombuyiselo, and a white Swiss-German, Robert Noah. This memoir follows Trevor from his early childhood through his developmental ups and downs and the challenges he faced while coping with the pressure inherent in Apartheid.

Patricia was no stranger to hardships. When she was 9 years old her father sent her to live with his sister in their impoverished Xhosa homeland called Transkei, crammed in with 14 cousins in unsanitary quarters without water and electricity. The children were required to work in the fields on a daily basis. Patricia managed to learn English in the local missionary school. Subsequently, she left for Soweto and enrolled in secretarial school. When Apartheid began to unravel, she moved to Johannesburg and was hired as a secretary for an international pharmaceutical company.

“I chose to have you kid, I brought you into this world, and I am going to give you everything I never had.”

Patricia and Robert met by chance in a white-only apartment building. It was illegal for black and white couples to have relationships and children. Patricia was a risk-taker and Robert Noah denounced apartheid. He was committed to the well-being of his son, but outings were risky for them. Whenever the couple thought it was safe, they went out for walks or to parks. Even though the Immorality Act of 1927 had been rescinded, police goon squads frequently roamed the streets hunting for alleged criminals. Children of mixed race were arrested and put in orphanages. Patricia was understandably terrified, so when the family went out, Robert walked on one side of the street while Trevor and Patricia had to be on the other side. When Patricia sensed that the police were nearby, she would put Trevor (whose skin was much lighter than hers) down and tell him to walk in front of her by himself. I can only imagine that family outings felt like a dangerous game of “hide-and-seek”. I wonder how Trevor felt during these separations. He was a precocious little boy and he most likely understood his mom’s directions. What personal meanings did he construct from these experiences? How did mother and son feel each time they reunited? Over time, Patricia found a safer way to take her son on outings. Trevor tells us that not only the color but also the shade of your skin was important in South Africa. Unlike black people, colored people, whose skin was lighter, could be seen with their colored children in public. Thus, Patricia paid a colored woman she knew to pretend to be Trevor’s mother while Patricia took the role of their maid. She also swallowed her pride and reached out to her mother and siblings to repair their three years of separation so that Trevor would grow up as a member of a real family.

Mother and Son

Trevor’s memoir suggests that he and his mother had similar temperament

styles. They were both very bright, energetic, and driven to get their own way whenever possible. I suspect that similarity in their personality types enhanced Patricia’s attunement to her son’s needs. Patricia knew they both needed structure and predictability in their life. Religion gave them community and structure. Patricia insisted that they attend two black churches and one white church each week. Trevor liked music and meeting other people so he enjoyed church with one exception. When they didn’t have money for gas, he pleaded with his mother to skip church rather than face a two hour walk to and from services. Unfortunately for Trevor, Patricia would not relent.

Young Trevor was quite social and wanted to play with other children, but his skin color presented a problem. Patricia worked, so his maternal grandmother became his primary babysitter. However, her next-door neighbor was known to report white kids to the police: they thought Trevor to be white and thereby not allowed to play with black children. Trevor wanted to go outside to play with his cousins and other children so he dug a large enough hole in the ground and got out to the street. His grandmother was terrified that he would be caught and the whole family would be arrested: so, she locked him in the house for his own safety. Patricia knew her son well and recognized how bored he would be without stimulation. She bought him books, toys, and games. He was a gifted child. Roald Dahl was his favorite author and he had all his stories as well as Narnia and other fantasy books. Reading nourished his vivid imagination and became his source of happiness that likely fed his mind and sense of humor.

Trauma

Trevor writes that he remembers all the frightening and traumatic events of his life, but they don’t bother him. Patricia schooled Trevor in the theory that it’s best not to become preoccupied with the past. As a psychoanalytically trained psychologist, I know denial may be a coping mechanism, but it doesn’t relieve the internalized pain and suffering. Trevor frequently describes himself as a ‘naughty boy’. I believe his propensity for serious kinds of trouble is a symptom of his internal distress. As a child, he was fascinated by knives, collecting them from pawn shops and garage sales. Trevor also loved fire and fireworks. He even figured out how to use gun power and, in one instance, he ‘accidentally’ dropped a match on it and burned off his eyebrows. Stealing chocolate and letting his friend take the blame. Bootlegging CDs and being arrested for it. His behavior excited him and fueled his need for attention. Patricia went through a series of tragic events when her son became a successful grown-up. Trevor has clearly written this book for his mother, but his need to protect her privacy and hide his own feelings often leaves us in the dark.

When I finished reading this book, I found myself asking the question: Will the real Trevor Noah ever appear? His humorous façade masks feelings he finds uncomfortable. His need to protect himself is evident in his interview with Howard Stern. When Stern asks about dating and whether Trevor thought about marriage, Trevor answers that he would consider getting married but his wife would have to agree to live in a separate house. In his provocative way, Stern pushes him to elaborate. Trevor becomes defensive as he tries to explain his approach to marriage. Interestingly, he switches into his comic-style voice used on his show perhaps to protect himself from feeling anger at Stern for exposing his vulnerability. I suspect he works hard to avoid personal exposure, not an uncommon dynamic for comedians.

I like to imagine what life would be for Trevor and his family if they lived in

Boston. In her article Psychological Repair: The Intersubjective Dialogue of

Remorse and Forgiveness in the Aftermath of Gross Human Rights Violations, a South African psychologist, Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, discusses similarities in challenges that black and interracial families face in different countries. The US inequities are not so different from those found in South Africa. What would Trevor’s life look like if he lived in Dorchester, Mass? Would he have more friends and continue in his mischievous ways with like-minded buddies? Would he allow himself to enter therapy to work on his traumatic past had mental services been available? We can only wonder. His story leaves us with appreciation of sincerity, optimism, and ardent depiction of life in South Africa.

Ellen Goldberg can be contacted by email here.

***

The opinions or views expressed on the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute (“BPSI”) social media platforms, including, but not limited to, blogs, Facebook posts and Twitter posts, represent the thoughts of individual contributors and are not necessarily those of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute or any of its directors, officers, employees, staff, board of directors, or members. All posts on BPSI social media platforms are for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as professional advice.

BPSI does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness or completeness of information contained in its contributors’ posts and/or blog entries, or found by following any linked websites. BPSI will not be liable for any damages from the display or use of information posted on its website or social media platforms. BPSI cannot and does not authorize the use of copyrighted materials contained in linked websites.