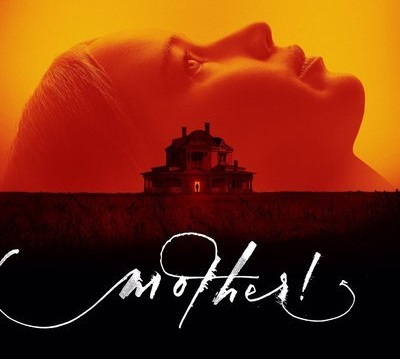

Below are the throwback remarks from the September 19, 2017 “Off the Couch” viewing of mother! with Rodrigo Barahona, PsyaD, Member of BPSI. “Off the Couch” is part of a decades-long collaboration between The Coolidge Cinema and BPSI.

A married couple (Jennifer Lawrence and Javier Bardem) share a quiet, mundane life in their isolated country home–that is, until they take in an eerie stranger (Ed Harris) and his provocative wife (Michelle Pfeiffer). As their guests become lodgers and her husband grows increasingly erratic, the woman’s frustration turns to foreboding. Visitors and the omens continue to multiply as the film crescendos to a bacchanal, hallucinatory climax.

First, few words about how I view this film from my point of view as a psychoanalyst, and then we can open it up to questions, thoughts, and your own psychological interpretations of what it was that we all just saw. As an analyst, I would use psychoanalytic theory as a way of listening to this film, as if I were hearing a patient narrating a dream in session or telling me about something that they had read about in a book or a confusing memory from long ago or a scene they breezed past and caught a glimpse of through the window on a train ride and could only remember certain vivid or blurry images. The images, words, and sequences may not make logical sense unless viewed or listened to sideways, what the Lacanian psychoanalyst and philosopher Zizek would call “looking awry”. You cannot get at its “truth” if you take it head on. A film shows the viewer images that cannot be taken at face value, in the same way as a patient’s symptom or an image in a dream contains (some analysts would say conceal, others would say processes, but in both cases, contains), something of the unthinkable, the unknowable, the unbearable. In mother! this is pictorialized in the scenes of the blood on the carpet. One moment the blood-stained carpet is moved to show nothing underneath, and the next moment it reveals a bloody hole. To gaze inside that hole is to gaze inside the abject, to use Julia Kristeva’s term, into the unconscious or more specifically, into the Real of the unconscious, the place where the unfathomable desire of the other resides. To gaze into that hole, into the underlying text of a film, is to gaze into chaos, and to invite the nameless, formless anxiety that the British psychoanalyst Bion described as nameless dread.

Why does this particular film exist at this particular moment in time? There is an assumption that has to be made, if one wants to think of a film psychoanalytically, that a film, like any other work of art, attempts to capture, render visible and digestible, the anxieties through which an individual and a culture are passing at that moment. Just as in a psychoanalytic session we might listen to a patient’s account of what happened in the past or of last night’s dream, as a story also about the present emotional moment, even a historical film—Lincoln, for example, appears on the scene to help us understand something about the here and now. Directors, like other artists, are chosen by society to help us with this work—so that we can sleep at night without waking but still wake up with enough of a sense of disturbance that we might enter the next day in a slightly different manner than the day before. Like a successful dream, successful films and their directors can do that. The psychoanalyst and social psychologist Enrique Pichon-Riviere would say that artists function like the portavoz, the “spokesperson” for a society, the speaker of that group’s anxieties and tensions. Poor films and poor directors, on the other hand, make sure we stay asleep throughout our lives.

“Looking awry” at a film, giving it a sideward glance, lifts it out of its three-dimensional space, we may say out of Euclidean space, and brings it alive in the field—call it the analytic field, the intersubjective field, the social-cultural-political field—in which we all interact in conscious and unconscious ways. Giving it an awry look can help us capture the form, the whole picture, even if just for a moment before it disappears back into the unconscious, where reside the things that we can’t speak or think out loud. Inside and outside, individual, collective human experience and film, weave into and around each other in ways that for brief moments, if we are able to step out and see ourselves in the film, can give us a glimpse into the turbulence that stirs beneath and indeed underwrites our very present day anxiety.

As is obvious to all of us I’m sure, this film is rich in symbols, some of them perhaps more explicit than others. The film enthusiasts among us might have already thought of other movies in association to this one, just as someone narrating their dream will immediately associate to past memories and images. Rosemary’s Baby is the most obvious, but how about Aronofsky’s first film, Pi, where the protagonist anguishes over divining the name of God or Aronofsky’s last film before this one, Noah? In fact, you might insert Noah in the middle of the two acts of mother!, The first act finalizes soon after Ed Harris (man) and Michelle Pheiffer (woman)−that impulsive couple that knows no limits−and sons leave the garden of Eden, having screwed it up by reaching for and trying to clasp His (Javier Bardem’s) desire—the unthinkable, unknowable, and untouchable source of all creation—as represented in the crystal, the fruit hanging in the office of life and knowledge. They are vanished once and disappear a last time after one of the brothers kills the other. But they return, with others, like hordes of animals flooding the arch, and here we have the theme first touched upon with Noah: of the patriarch/psychopathic tyrant who recreates the earth by destroying it. But before this—does He take some pleasure in watching one son destroy the other? Aronofsky seems to imply he does. Is that, then, critical to creation, this type of merciless, backstabbing, one may say boardroom, competition? Did He actually enable this, shall we say, desire this? Bardem’s He tells Jennifer Lawrence’s Mother that he held one son’s hand as he died. Mother seems perturbed, deeply saddened. He, on the other hand, seems inspired. Sexual excitement is implied, but when Mother goes to “join him” upstairs, He is fast asleep. The hordes of people continue to come into the house, like biblical plagues or masses of refugees or CNN news alerts on your phone. Mother does not know what to think, and He gaslights her over and over. An entitled man sexually accosts Mother, who rejects him. He calls her a “cunt” and tries to guilt her, as she “doesn’t even know” him (another example of gas lighting, a word that we have all become overly familiar with during the past year and a half). Finally, there is a catastrophic flood in the kitchen and everyone and everything is washed away. Furious, Mother provokes Him by pointing out His impotence in the act of creation (He can’t “fuck” or write) and in an act of what can only be interpreted as narcissistic repair and aggressive appropriation, He finally “fucks” a deprived and tortured Mother. As if by magic, a baby is instantly conceived.

Two other films come to my mind in association to mother!, and they must form part of the collective chain of anxieties that has been coming together now for at least the past decade, before the present moment in this country and the world that the film, in my reading, is trying to represent. These are Melancholia and Antichrist, both by Lars Von Trier, and both have to do with the crashing down of the patriarchal order. Antichrist, also about a couple alone in a cabin in the woods (similarly, their names are He and She), deals with some of the themes worked on here, though if Antichrist was a film about the fall of the father, the paternal, and a deconstruction of the patriarchal myth of the eternal feminine, where woman is expected to be a passive, angelic, baby-producing machine in order to fully exist in the social order (She’s depression in that film is seen by He, incidentally a CBT therapist, as a sign of illness rather than of revolt against the patriarchal order), medicating her abject feminine desire in order to not terrify and destabilize the patriarchal system, mother! might be thought of as representing the reactionary backlash we are experiencing today, where the fallen symbolic father returns in his real and vulgar, one might even say ridiculous but terrifying form. In this reading, Make the Father Great Again might be the working title of this film. Mother herself seems to only wish for a baby, as if confirming Freud’s thesis that a little girl’s wish for her father’s baby quenches the powerless feeling of forever being in lack. As we learned in the last election, as in the Victorian times of Freud, there is no place for an aggressive woman in this social-political-cultural order. Mother does attempt to assert her authority, but she is forever treated like a child. Thus, she self-medicates. What is it about female desire that so terrifies, may we say, repulses Him?

The analyst Bion would say that one film, mother! is the transformation of the previous one, Antichrist, and that each and all are transformations of a present, current anxiety. The viewer, as a psychoanalyst, is invited to notice the invariants between them—and within themselves as they interact with the film—what doesn’t change, what is repeated but in a slightly modified form. In these invariants one finds the form, the “O” as Bion would call it, something approximating, again, if only for a second and a glimpse, the unconscious. Freud would call this the navel of the dream. The place where it all comes together, and if unraveled, all comes apart. This place is abject, we cannot see it directly, though it pulls us in and repels us all at once (An example of this is staring at the sun during a solar eclipse. It is well known that only magical, omnipotent beings are capable of doing this without special glasses). In the film, it is the hole underneath the bloodied carpet, or the hole in man’s back from which the rib of life, death, envy, greed, desire, lust, and destruction are born. It is the (w)hole from which the unfathomable desire of the Other (immigrants, neo-Nazis, the Obamacare repeal) unceasingly pulsates and into which we are constantly feeling pulled, to bring up a psychoanalytic theory of anxiety as having to do with the terror of being pulled into the insatiable void of the Other’s desire. In mother!, the doorbell doesn’t stop ringing. It’s Harvey. Then its Kelly Anne Conway. The doorbell rings again and it’s a mob of entitled drunken frat boys, followed by refugees, the police, Syria, Irma. Mother, finally, has enough. We ask the question, “Who has the right over a woman’s body?” However, the last word goes to Him. Finally, in an enigmatic scene at the end of the film, He removes Mother’s heart in order to transform her desire into his ability for omnipotent, magical, and sexless creation. We may ask ourselves, is He appropriating her right to protest?

Rodrigo Barahona, PsyaD, is a faculty member at the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute, a board member of the Boston Group for Psychoanalytic Studies, and a member of the American Psychoanalytic Association and the International Psychoanalytic Association. He is also a committee member on the IPA/IPSO Relations Committee Committee and an associate board member of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis. He has a private practice in Brookline, Massachusetts. Dr. Barahona regularly reviews Latin American psychoanalytic literature. Click here to check out his other recently published reviews.

Rodriogo Barahona can be contacted by email here.

***

The opinions or views expressed on the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute (“BPSI”) social media platforms, including, but not limited to, blogs, Facebook posts and Twitter posts, represent the thoughts of individual contributors and are not necessarily those of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute or any of its directors, officers, employees, staff, board of directors, or members. All posts on BPSI social media platforms are for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as professional advice.

BPSI does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness or completeness of information contained in its contributors’ posts and/or blog entries, or found by following any linked websites. BPSI will not be liable for any damages from the display or use of information posted on its website or social media platforms. BPSI cannot and does not authorize the use of copyrighted materials contained in linked websites.