Below are the remarks from the February 20, 2018 “Off the Couch” viewing of The Insult with Mary Anderson, PhD, MTS, MFA, Member of BPSI. “Off the Couch” is part of a decades-long collaboration between The Coolidge Cinema and BPSI.

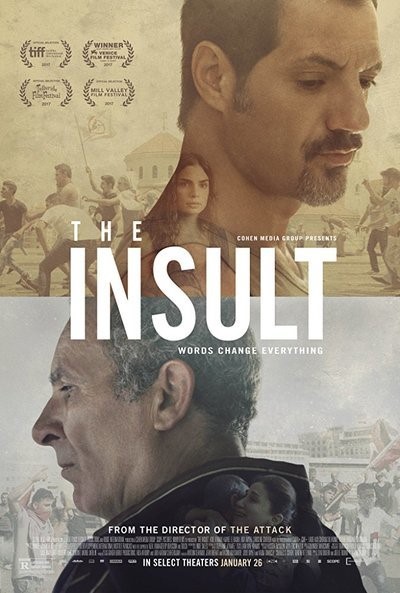

In today’s Beirut, an insult blown out of proportions finds Toni (Adel Karam), a Lebanese Christian, and Yasser (Kamel El Basha, winner of the Best Actor prize at the Venice Film Festival), a Palestinian refugee, in court. From secret wounds to traumatic revelations, the media circus surrounding the case puts Lebanon through a social explosion, forcing Toni and Yasser to reconsider their lives and prejudices.

On July 30, 1932, as part of a League of Nations proposal, Albert Einstein wrote to Sigmund Freud inviting him to respond to a question that, he states, “seems the most insistent of all the problems civilization has to face.” “Is there,” Einstein asked, “any way of delivering mankind from the menace of war?”1 Freud’s response addressed evolutionary, historical, cultural, biological and psychological factors at play in the human compulsion to wage war, all of which echo and trace the ambivalent nature of the human psyche, the intertwining of the drives for life and death, eros and thanatos, which manifest in human love, sexuality, and aggression. Civilization of human life, Freud avered, requires a progressive displacement, restriction and sublimation of our instinctual aims and impulses. Much later, Freud’s daughter, Anna, herself a noted British child psychoanalyst, would confirm her father’s thesis in writing: “The two fundamental instincts combine forces with each other or act against each other, and through these combinations produce the phenomena of life.”2

In Ziad Douieri’s “The Insult” we witness these “phenomena of life” poignantly portrayed in the lives of Tony Hanna, a Lebanese Christian who is an automobile mechanic, and Yasser Salameh, a Palestinian Muslim who works as a construction foreman. In their lives and interactions we see the combined, intricately intertwined yet conflicted forces of love and aggression play out on a psychical, interpersonal, familial, socio-political, and historical stage.3 In Tony and Yasser’s caustic exchange over the old, now illegal, drainpipe we see the conscious and unconscious expression of aggression that is both a part of, and in conflict with, the erotic instinct and its effort to sustain life. Its seemingly other side, the destructive instinct, is, Freud writes to Einstein, “at work in every living creature, striving to bring it to ruin, reducing life to its original condition of inanimate matter.”4 In Tony’s actions we see his internal conflict writ large: by routinely and perhaps, unconsciously, caring for his home – cleaning the balcony – he spews insult on those who encroach upon it, upon his and his family’s sense of security and wellbeing. The illegal drainpipe, its seemingly indiscriminate and untimely spewing of dirty water on the heads of Yasser and his workmen below, is a keyhole, a metaphor, through which we see the personal, political, legal and religious tensions of Ziad Douieri’s film unfold.

War, this film seems to say, exists in the particular – within the individual person. It is intimate and its affective wake arises, becomes visible and magnified, as it moves outward onto objects, persons, environments. The film brilliantly, and ambivalently, situates the viewer to see not only that war begins with individuals – in the everyday ‘insults’ that occur between and within people. It also incisively traces war’s path between the individual human psyche and the cultural environment. Ziad Douieri accomplishes this tracing cinematically, in part, through the selective and empathic use of flashbacks, where, in fragments – shards of traumatic recollection – we experience Tony’s escape from his besieged childhood home in Damour, via the train tracks, carried by his father. As the film unfolds we feel Tony’s conflict, the silent yet raging grip of his early childhood trauma and its resurgence during the ensuing litigation, heralding the necessity of change, for Tony’s letting go, for his turning the page in order to live.

With the judge in Tony’s first legal suit we, the viewers, “don’t believe this all started by a gutter.” Yet it is through this ‘gutter’, what it symbolizes and represents, that we come to understand ‘the insult’ on multiple levels, its meaning piercing several human registers of feeling. What begins in the violence of acts and words – the anger and defense of a curse, the repair and destruction of a drainpipe – escalates to reveal the intricacy of conflicting identifications within an individual life: Tony Hanna’s idealization of and alliance with the Lebanese Christian political platform while stating outright, “I’m no Jesus Christ who will turn the other cheek”; and Yasser Salameh’s unwillingness to repeat Tony’s hate speech, “I wish Ariel Sharon had wiped you all out,” in court despite his insecure status as a Palestinian refugee, working illegally.

Yet while the film shows us, repeatedly, how war foments and why war exists – in me, in you, between people and nations – it shows, at the same time, what keeps war at bay, what Freud writes of as eros, love, that which encourages “the growth of emotional ties between men” [sic.].5 It is here that Douieri’s subtlety and humor shine amid the polemic tension, when, for example, we hear Tony’s preference for autoparts from Germany over China reiterated in Yasser’s preference for the $800. per day Liehber crane over the cheaper Chinese model; or when we see Tony, a mechanic, defer to Yasser’s opening his car door first and his returning to fix Yasser’s car when it won’t start.

It is, near the end of “The Insult,” that we see the intimate, interpersonal resolution of individual and intergenerational trauma enacted, in what Freud described as a “remembering, repeating and working through.”6 Following the public exposure of Tony’s childhood trauma at Damour in the courtroom proceedings, Yasser returns to face Tony at his garage. Flogging Tony with a slew of insults that incite Tony to punch him, Yasser then apologizes. In this repetition of Tony’s earlier ‘apology’ to Yasser, we recognize as if in a mirror the terms on which reconciliation between these two men depends. Rather than an “eye for eye … wound for wound, stripe for stripe” (Exodus 21:24) or its Christian revision: “if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also” (Matt. 5:38-42) we see enacted instead, between Tony and Yasser, a paradoxical, egoic, male quid quo pro – a brutal yet oddly tender revising of the biblical: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” (Luke 6:31; Matt. 7:12).

1 “Why War? An Exchange of Letters between Freud and Einstein (1933): International Institute of Intellectual Co-operation (League of Nations). Trans. Stuart Gilbert. Warum Krieg? Paris: Internationales Institut für Geistige Zusammen-arbeit (Völkerbund). Reprinted as “Why War?” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. XXII (193201936): New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis and Other Works, pp 195-216. James Strachey writes: “It was in 1931 that the International Institute of Intellectual Co-operation was instructed by the Permanent Committee for Literature and the Arts of the League of Nations to arrange for exchanges of letters between representative intellectuals ‘on subjects calculated to serve the common interests of the League of Nations and of intellectual life’, and to publish these letters periodically. Among the first to be approached by the Institute was Einstein and it was he who suggested Freud’s name. Accordingly, in June, 1932, the Secretary of the Institute wrote to Freud inviting his participation, to which he at once agreed. Einstein’s letter reached him at the beginning of August and his reply was finished a month later. The correspondence was published in Paris by the Institute in March, 1933, in German, French and English simultaneously. Its circulation was, however, forbidden in Germany,” p. 197-8.

2 Anna Freud, “Notes on Aggression” in Indications for Child Analysis and Other Papers 1945-1956 in The Writings of Anna Freud, Vol. IV (New York: International Universities Press, Inc. 1968): 67.

3 Worth noting here are the parallels between film and life: Douieri, who was raised in a Muslim family, co-wrote “The Insult” with Joelle Touma, who was raised in a Lebanese Christian family.

4 Sigmund Freud, “Why War?” p. 211.

5 “Why War?” p. 212.

6 See, Sigmund Freud (1914) “Remembering, Repeating and Working Through (Further Recommendations on the Technique of Psycho-Analysis II).” SE XII, pp. 145-156.

Mary Anderson, PhD, MTS, MFA, is an interdisciplinary artist-scholar, writer, educator and consultant, working at the intersections of philosophy, theology, ethics, aesthetics and psychoanalysis. Her consulting practice focuses on the ethical and aesthetic articulation of meaning in human life and art. A recent graduate of academic candidate training at the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute, Dr. Anderson coordinates the Global Humanities Curriculum project at the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard. She is currently writing a series of essays on representation and the ethical ‘turn’ within human consciousness

Mary Anderson can be contacted by email here.

***

The opinions or views expressed on the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute (“BPSI”) social media platforms, including, but not limited to, blogs, Facebook posts and Twitter posts, represent the thoughts of individual contributors and are not necessarily those of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute or any of its directors, officers, employees, staff, board of directors, or members. All posts on BPSI social media platforms are for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as professional advice.

BPSI does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness or completeness of information contained in its contributors’ posts and/or blog entries, or found by following any linked websites. BPSI will not be liable for any damages from the display or use of information posted on its website or social media platforms. BPSI cannot and does not authorize the use of copyrighted materials contained in linked websites.