Shari Thurer, ScD, is a BPSI Psychotherapist Member. Her below remarks originally appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of the library newsletter, which can be read here.

What is it like to grow up as the child of a Nazi? How does it feel to share genetic material with fathers who orchestrated the extermination of millions of innocent people? “Like father, like son,” we say. But are the sins of the fathers visited upon their offspring? The Old Testament, Euripides, Horace and Shakespeare would have us believe that bloodlines are destiny. Of course, modern thinkers reject these ideas as unscientific, though a shadow of them may remain in our collective unconscious. So, what was the fate of the Nazi children, who, after the fall of National Socialism, found themselves facing the monstrous reality of their parents’ complicity? How do these folks cope with the immense cognitive dissonance of knowing that the hand that rocked their cradle perpetrated the Holocaust.

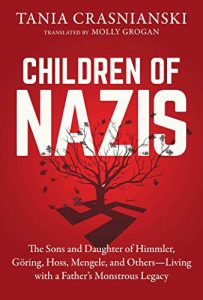

French lawyer, Tania Crasnianski, explores this question in her book Children of Nazis in which she presents the portraits of eight offspring of the Third Reich leaders – the grown-up children of Himmler, Göring, Hess, Frank, Bormann, Höss and Mengele. She had hoped to meet her subjects in person, but in the end, she interviewed only one: Nicholas Frank, and had to rely on extensive research to describe the others. In 1940, she tells us, the German offspring of the Nazi elite were privileged little aristocrats. They were raised by caring, affluent parents and nannies. For them, the Nazi defeat was an earth-shattering family rupture, an alarming fall from grace, abrupt downward mobility, and a jarring discovery of Hitler’s atrocities. Some children of Nazis, such as Himmler, Göring and Höss, despite knowledge of their fathers’ barbarism, could not stop idealizing them, spending their lives trying to repair their fathers’ reputations. Others, like Bormann’s and Frank’s sons, vociferously condemned them. Crasnianski sensibly attributes the difference to the strength of their early bond. The psychoanalytic reader may find these accounts less than nourishing as there are no psychodynamic conjectures or explanations of these Nazis’ children’s behavior, merely objective descriptions. But, given the restrictions on her research, the author did a commendable job collecting and organizing the information available. This book is a meaningful addition to knowledge about the long-term consequences of evil.

Shari Thurer, ScD, is a BPSI Psychotherapist and Library Committee Member, a former Adjunct Associate Professor at Boston University, a psychologist in Boston, and the author of many noted publications, including Myths of Motherhood: How Culture Reinvents the Good Mother (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1994) and The End of Gender: A Psychological Autopsy (Routledge, 2005).

Shari Thurer can be contacted by email here.

* * *

The opinions or views expressed on the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute (“BPSI”) social media platforms, including, but not limited to, blogs, Facebook posts and Twitter posts, represent the thoughts of individual contributors and are not necessarily those of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute or any of its directors, officers, employees, staff, board of directors, or members. All posts on BPSI social media platforms are for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as professional advice.

BPSI does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness or completeness of information contained in its contributors’ posts and/or blog entries, or found by following any linked websites. BPSI will not be liable for any damages from the display or use of information posted on its website or social media platforms. BPSI cannot and does not authorize the use of copyrighted materials contained in linked websites.