Ellen Goldberg, PhD, is a BPSI Psychotherapist Member. Her below remarks originally appeared in the “What Are We Watching” section of the Spring 2020 issue of the library newsletter, which can be read here.

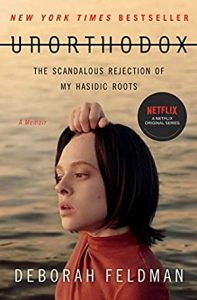

“Unorthodox” is a four-part Netflix mini-series loosely based on a memoir by Deborah Feldman. Ms. Feldman successfully left the Satmar Hasidic sect, which is considered one of the wealthiest and most powerful communities in Williamsburg. The film’s protagonist, Esty Shapiro, prepares, at the age of 19, for her escape from Yanky, her husband, who has asked for a divorce because of her infertility. Esty’s departure creates a scandal. She must be brought back to her community at all costs. After consultation with the head Rebbe, her immature husband Yanky and Moishe, a prodigal son with a penchant for gambling and booze, go to Berlin to bring her back home. In some ways, this mini-series reminds me of a thriller. The portrayal of the wedding and other rituals is accurate in its depiction of both the beauty and the stiffing rules infused in daily living. I found the scene when Yanky and Esty met for the first time evocative of developmental issues of adolescents. Yanky tells Etsy that his father took him and his brothers to Europe to visit the graves of famous Hasidic Rabbis. Esty asks him if they visited anywhere else. Yanky responded that he had asked his father if they could go to Paris, but his father said “no”. In the same scene, Esty is encouraging of his wish, “maybe another time.” She also lets him know that she is different than the other young married women in the community. In some ways, Yanky’s ability to share his wishes and her response would not be considered unusual for adolescents.

Since Deborah Feldman was able to get a college degree and become a successful author, I was curious to learn more about her life. I read her memoir Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots (Simon & Schuster, 2012). Because Deborah was an only child, her devoted grandmother was able to give her a lot of love and attention. It appears, her grandmother tacitly gave her psychological space and opportunities to explore Williamsburg beyond the boundaries of the Hasidic community. Although it was not discussed between them, it is likely her grandmother knew of her granddaughter’s access to the public library and her love of reading. Years of attention meant better ego development and energy. Feldman’s exposure to literature and ability to negotiate a life beyond the walls of her Hasidic community served her well. Esty of the TV series was similarly lucky: unlike other girls, she had an exclusive love and full support of her grandmother. An average number of kids in a typical Hasidic family can be anywhere from 8 to 12 children, so many youngsters are less likely to get such exclusive attention. This love, however, is constraint by the cultural norm that insisted the needs of the community prevail over personal desires. I believe the rigidity of the community is reinforced by the Holocaust inter-generational trauma. References to Holocaust are invoked in the scene of the Passover prayer and many times throughout the film.

Only 2 to 3 percent of young Hasidic adults leave their community. Unfortunately, they find it very difficult to break away, because they do not have the financial resources. Since they go to private schools that primarily teach Yiddish and Torah to males and only Yiddish and marital duty to girls, women have limited capacity to support themselves. Without an understanding of broader social and cultural values, they struggle in the American society. Women who dare to leave the community either loose custody of their children or end up with limited visitation rights as they cannot afford high quality lawyers. From what I have found thus far, Deborah Feldman is the only post-Hasidic woman who has been able to gain full custody of her child.

Having been raised in the Orthodox Jewish community post World War II, I was always aware of the variety of ways Jewish beliefs were celebrated. Some, like my family, verged on conservatism, while others were extremely Orthodox. Esty reminded me of teenage girls that I worked with in the past. They had feisty rebellious personalities and pushed the envelope trying to follow their own desires rather than rigid rules of their communities. I continue to be interested in the complexities of the Hasidic families who all too often resort to defensive denial in order to protect family secrets and the primacy of the group.

Ellen Goldberg, PhD is a Psychotherapist Member of BPSI. She has a private practice in Newton, MA and she is on the faculty of the Brenner Center at William James College.

Ellen Goldberg can be contacted by email here.

***

The opinions or views expressed on the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute (“BPSI”) social media platforms, including, but not limited to, blogs, Facebook posts and Twitter posts, represent the thoughts of individual contributors and are not necessarily those of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute or any of its directors, officers, employees, staff, board of directors, or members. All posts on BPSI social media platforms are for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as professional advice.

BPSI does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness or completeness of information contained in its contributors’ posts and/or blog entries, or found by following any linked websites. BPSI will not be liable for any damages from the display or use of information posted on its website or social media platforms. BPSI cannot and does not authorize the use of copyrighted materials contained in linked websites.