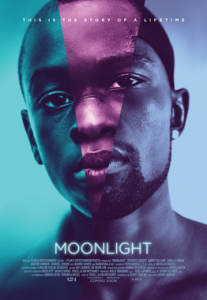

Find out what what said about MOONLIGHT at November’s Off the Couch.

Moonlight: Talk for Off the Couch

by Judith A. Yanof

First, a bit of background: Moonlight is an independent film, written and directed by Barry Jenkins. It is the second feature film by this 36 year-old writer/director. The story is taken and adapted from an unproduced play by Tarell Alvin McCraney, “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue.” The story is set in the 1980s in Liberty City, a poor black neighborhood of Miami, and shot on site. Interestingly, both Jenkins and McCraney grew up in the projects of Liberty City, 4 blocks apart, and went to the same elementary and middle schools. But they never met until they were adults, brought together by this project. The movie is semi-autobiographical for both men. Both had mothers who were crack addicts. McCraney is gay. Jenkins is straight.

Moonlight is unusual in that it does not have the arc of a conventional film with typical plot turns and twists. Told in three chapters, the story is moved along by the unique unfolding of a particular life, with its particular continuities and discontinuities, much in the same way as in Richard Linklater’s Boyhood. And, while Moonlight captures Chiron’s world in very specific detail and never minimizes the impact of his real life circumstances, Jenkins’ filmmaking gives the audience a sense of living inside his main character’s internal experience rather than documenting it. (I am thinking here of the camerawork – the way you feel like you are in the water with Chiron when that little boy learns to swim. Or the way voices fade out, when Chiron cannot stand to hear his mother yell at him. I am thinking about the visual imagery – the way water is used as a recurring symbol of healing and renewal, or the way the camera returns to the ocean for moments of human connection and relief from the ugliness of Chiron’s world. I am thinking of the eclectic soundtrack.) All these things give the movie a dreamlike quality, almost as if the film is a series of associative memories, rich and sensual, but not exactly linear.

In the end we have gotten to know a person – a person who is excruciatingly lonely and vulnerable, a person who finds it immensely difficult to connect to others, someone who has been damaged by his circumstances, but someone who has somehow eked out some tenderness and goodness from a blighted surround, and someone, who, at the end, seems to be able to summon the courage to try once more. This personal story touches us and transcends the particulars.

This is a movie about identity, not simply gay identity, though certainly that is a very important part of who Chiron is, but identity in general. What is it to be a boy? A man? A black man? A person from a community that is marginalized? What is masculinity? Who is Chiron? How do you know who you are?

At the beginning Juan tells Chiron, “At some point you gotta decide who you are going to be. Can’t let nobody make that decision for you.” At the end Kevin asks, “Who is you, Chiron?” For much of the movie, Chiron is trying to come to grips with just this question.

Of course, when you are a child, the way you know who you are has everything to do with what you see in your parents’ eyes when they look at you. When you are a child, it is terribly difficult to separate who you really are from their construction of you. Chiron is neglected and entirely invisible to his mother, except when he is on the receiving end of her rage, a rage that she projects onto him, born from her own sense of failure and self-hate. Juan, the drug dealer, and Theresa, his girlfriend, are the closest thing to loving parents Chiron has, and this has an enormous impact on his life. But Juan is gone by the second act.

The recurrent issue of naming and renaming is a touchpoint in this movie. And names are identity. When Jenkins wrote the screenplay, he restructured the play into three chapters. Each chapter has a title – each title a different name for the main character: Little, Chiron, and Black. Chiron is the main character’s given name. Little is the name he is called by his latency-aged peers: a nickname, a name that describes him, but also a name that diminishes him. Black is the name he is given by his friend Kevin, who sexually connects with him and later betrays him as an adolescent. And Black is the name he has chosen for himself as an adult. The meaning of the name Black is unclear and likely ambivalent, but it is one way that Chiron keeps Kevin with him.

Chiron asks Juan and Theresa what “faggot” means. Faggot is another name. Juan says “Faggot is a name that is meant to make gay people feel bad about themselves.” It is the rejection and hostility of that naming that Chiron takes in, without even knowing what the name means.

What Chiron does know is that he is different from the other boys. He does not know that he is gay. But he does know that he wears his masculinity in a way that is different from his male peers. Their way of seeing him as “other” also contributes to how he sees himself. Latency-aged boys are invested in who belongs and who doesn’t belong to their rather rigid, stereotyped definition of being male. Boy culture at this age is largely homophobic, and not just in Liberty City.

By the time Chiron is an adolescent and struggling to come to grips with his own sexuality and desire, he is completely shut down because he is the victim of destructive, violent gay-bashing at school. He is silent; he is stoic, keeping his rage locked up. When betrayed, he snaps: he lets out a murderous rage.

In the final chapter, Black is unrecognizable to us. When we first see him, we think for a moment that we are seeing Juan: the build, the diamond studs, the do-rag. Black says that he has made himself over from the ground up. Black’s body has become his armor. It’s his safety. It is his protection. However, as we come to learn, this beefed-up body is also an impenetrable wall, keeping others from touching him. And he does not touch himself. He is completely disconnected from his own body – its desires, its longings, its needs.

Black seems to have taken on the identity of Juan, wholesale, without understanding the real reason he has done that – without realizing that it was the tender connection to Juan that he values and longs for, not Juan’s outside persona. By walling off the parts of himself that were vulnerable and painful, Black has also walled off any meaningful connection to Little, to Chiron, to his past, to his inner world. He has not been able to create a continuous identity nor to tell his own story. He has not been able to think about why he has become the way he is and, therefore, to know how to get to where he wants to go.

At least not until he reconnects with Kevin, when something begins to unfreeze inside him. As he drives to see his friend, whom he has not been in touch with for a decade, Caetano Veloso’s rendition of Cucurrucucú Paloma is heard in the background. The song transported me back to another great movie – a very different movie – Almodóvar’s Talk to Her, in which this haunting song about a lover pining for his lost love has a central place. In that film, too, talking is difficult and the main characters, two men, are unable to acknowledge the depth of their feelings for each other.

One of the most interesting things about this film is what is not said. Words have never come easily to Chiron. As a child he is almost mute. As an adolescent he seems to want to be invisible. Silence represents not only that which is held back, but also that which is not articulated, even to the self. In the final chapter, his dialogue with Kevin, which is the film’s highlight, seems to occur in slow motion. Everything about their conversation is understated, except that which they communicate nonverbally. In the background another evocative song is on the jukebox, Barbara Lewis’s 1963 Hello Stranger.[1] The two men circle round and around, awkward, with long silences between them, trying to find a way to say that they care for each other. And in the end they do. For that moment, at least, Chiron has found his voice.

[1] Hello Stranger lyrics:

Hello, stranger

Ooh It seems so good to see you back again.

How long has it been?

Ooh, it seems like a mighty long time….

Oh-aah-uh-oh

If you are not going to stay

Ooh Please don’t treat me like you did before

Because I still love you so a-a-

Although

It seems like a mighty long time

Shoo-bop, shoo-bop, my baby, ooh.